- Home

- Emily Carr

Emily Carr

Independent Spirt, Adventurer, Painter, and Writer. Her works are among the most coveted of Canadian artists

Emily Carr was one of the preeminent Canadian painters of the first half of the 20th century. She is regarded in the same esteem as the Group of Seven. Carr is remembered primarily for her painting. She was one of the first artists to attempt to capture the spirit of Canada in a modern style. She was one of the only major female artists of the period in North America or Europe. Someone believe she was the most original. She is known for her bold depictions of nature and for images of the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast.

She regarded her subject matter and, more largely, her art as a force in the construction of what she perceived to be authentic Canadian national identity.

Emily Carr in San Francisco around 1890

Emily Carr in San Francisco around 1890

Beginning in 1890 she studied at the San Francisco Art Institute for two years before returning to Victoria. In 1899 Carr traveled to London, where she studied at the Westminster School of Art.

Carr took a teaching position in Vancouver at the 'Ladies Art Club' that she held for no longer than a month – she was unpopular amongst her students due to her rude behavior of smoking and cursing at them in class, and the students began to boycott her courses.

In 1910, she was determined to find out what the new modernist art was all about. Courageously she used her saving to travel to France with her sister Alice. The radical experiments in cubism and fauvism then being undertaken by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse and others in Paris weren’t for her. But she developed her own bold, colourful, post-impressionist style of painting. Carr then spent some time in France. After her return to Victoria in 1912.

Carr decided to make a visual record of Indigenous totem poles in their village settings before they disappeared.

“I glory in our wonderful west and I hope to leave behind me some of the relics of its first primitive greatness. These things should be to us Canadians what the ancient Briton's relics are to the English. Only a few more years and they will be gone forever into silent nothingness and I would gather my collection together before they are forever past.”

She made an ambitious six-week trip north to the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii) and the Skeena River. She was highly inspired during this trip, saying of the totem poles,

“How tightly they sealed their secrets from me. Humble and pleading before the great trees… awaiting the invitation from the spirit to come meet me halfway…Nothing is still now. Everything alive. At last, I knew I mist see through the eye of the totem itself. The mythic eye of the forest.”

There she documented the art of the Haida, Gitksan and Tsimshian peoples. The drawings and water colours she made on this and later trips gave her the source material for one of the two great themes of her painting career: the material presence of Indigenous cultures of the past.

Carr virtually lived among the indigenous people enduring mosquitoes, seasickness and several serious illnesses. Her adventurous trips in search of this material also led her more deeply into her second great theme: the distinctive landscape of Canada’s West Coast.

This is my country. What I want to express is here. And I love it! Amen.

By 1913, she had produced a substantial body of distinguished work. But with no one encouraging or supporting her she could not make a living as an artist. She built a small apartment house in Victoria for income. For the next 15 years, she managed the apartment and painted little. She also hooked rugs and bred sheepdogs to make ends meet.

“Cumshewa seems always to drip, always to be blurred with mist, its foliage always to hang wet-heavy ... these strong young trees ... grew up round the dilapidated old raven, sheltering him from the tearing winds now that he was old and rotting ... the memory of Cumshewa is of a great lonesomeness smothered in a blur of rain.” Carr wrote in her memoir Klee Wyck. Klee Wyck meaning Laughing One was the name given to her by Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people.

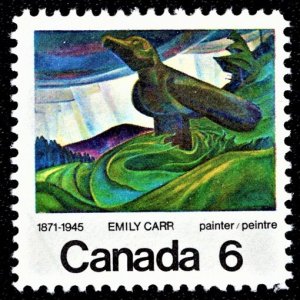

The Big Raven oil on canvas painted by Emily Carr, 1931

The Big Raven oil on canvas painted by Emily Carr, 1931

After suffering a heart attack in 1937 she didn’t have the energy for her field trips and painting. She spent more time writing. Her first book, the memoir Klee Wyck was a collection of stories based on her experiences with Indigenous people. It was published in 1941. She received the Governor General’s Award that same year.

Carr’s career took off when she was 57 years-old. Her work was brought to the attention of the National Museum and the Director of Canada's National Gallery, to visit Carr in 1927. It took a male ethnologist, Marius Barbeau who found her works to convince the museum and gallery to pay attention to her work.

The national Gallery Director visited Carr in 1927 and invited her to be part of an exhibition on West Coast Aboriginal art. She sent 26 oil paintings along with samples of her pottery and rugs with indigenous designs.

More exhibition requests were received after that along with an occasional sale, though never enough to improve her financial situation. She also was criticized as appropriations of Indigenous culture, but continues to be considered a master throughout the world. Laura Cumming, the art critic for the The Observer called her “Canada’s very own Van Gogh” while reviewing a 2014 exhibition of Carr’s work in London.

In 2013 her painting The Crazy Stair (1931) sold at auction for $3.39 million dollars. At the time it was the highest amount paid for a work by a Canadian female artist and the fourth most valuable piece ever sold in Canadian art auction history. In 2021 several of her painting sold for over $3 million. Cordova Drift (1931) sold for $3,361,260.

Canada Post issued a stamp commemorating Carr in 1971

Canada Post issued a stamp commemorating Carr in 1971

Learn more about Emily Carr, woman behind the art!

Books

Carr is also remembered for her writing, largely about her native friends. In addition to

Klee Wyck (1941)

The Book of Small (1942),

The House of All Sorts (1944), and, published posthumously,

Growing Pains (1946) an autobiography,

Pause (1953),

The Heart of a Peacock (1953), and

Hundreds and Thousands (1966).

Online collection at the Royal British Columbia Museum

https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/about/explore/featured-collections/online-emily-carr-collection

Archives

Royal British Columbia Museum

Timeline of her life

https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/visit/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/emily-carr-timeline

Documentaries

Winds of Heaven - Emily Carr, the Carver, and the Spirits of the Forest.

Canadian Artists Series – Emily Carr (1946)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JrWjhWY5jY&ab_channel=NFB

Emily Carr heritage minute

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wEbpE3YLlfE&ab_channel=HistoricaCanada

Emily Carr’s Artistic Celebration of the First Nation from Expert Voices by Sotheby’s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=90Ncc6HlWJU&ab_channel=Sotheby%27s

Exploring the art of Emily Carr with Dr. Kathryn Bridge, Royal BC Museum

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0auqjQvSR5Y&ab_channel=RoyalBCMuseum

News

Emily Carr report on CBC

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zF9xukHeJNc&ab_channel=CBC

Film

The Pines of Emily Carr (2005)