- Home

- Daphne Odjig

Daphne Odjig

Champion of indigenous art

Did you know there is a group of Indigenous artists that are known as the Indian Group of Seven?

.jpg) (September 11, 1919 – October 1, 2016)

(September 11, 1919 – October 1, 2016)

They formed in 1973, under their professional name - Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporation (PNIAI). They wanted to raise the profile of Indigenous artists to the same level of recognition as the Group of Seven who became the image of Canadian art in the early 20th century.

In 1972 Daphne Odjig was part of a 1972 exhibition of indigenous art in Winnipeg. The artists were trying to position their works as fine arts rather than simply ‘craft’. The show brought Indigenous art to mainstream Canadian audience.

Following that exhibition Odjig became the driving force to create PNIAI out of her home in Winnipeg. She invited Alex Janvier, Jackson Beardy, Eddy Cobiness, Norval Morrisseau, Carl Ray and Joseph Sanchez to discuss their mutual concerns about art. The group provide them with both community as well as a place their works could be analyzed.

They formally incorporated in 1973 funded by the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs.

It was Winnipeg Free Press reporter Gary Scherbain who nicknamed the PNIAI, the "Indian Group of Seven", referring to the Group of Seven of the 1920s and 1930s who painted Canadian landscapes in an impressionistic style.

Beside combined forces to promote Aboriginal art into the Western art world, they wanted to change the way the world looked at their art. They wanted a shift from an emphasis on "Indigenous (Native)" to "artistic" value and recognition. Their objectives were:

to develop a fund to enable artists to paint,

to develop a marketing strategy involving prestigious commercial galleries to exhibit their work,

to travel to aboriginal communities to stimulate young artists, and

to establish a trust fund, using a portion of the sales of artworks, for scholarship programme for emerging artists.

These goals were ambition for the time when Aboriginal peoples had only recently been given voting rights and they were fighting for civil rights. With these ideals, they were part of a movement which also included the "Triple K Co-operative Incorporated", a Native-run silk-screen organization which was established around the same time.

Although the group was together only briefly, their organizing was a crucial step in the development of the concept of Indigenous Native art as part of the Canadian cultural art world. The group has paved the way for younger generations to have their art professionally recognized.

Odjig’s championing of Indigenous art was fueled by the racism she experienced growing up. She began her career focusing on European masters. She taught herself to paint by copying pieces from the Royal Ontario Museum. Her early work showed influences of Picasso, Mattise and the impressionists.

As a young adult she encountered racial discrimination and faced barriers to employment because of her Anishinaabe name and appearance. Because of this she called herself Daphne Fisher and supressed her Indigenous identity.

Everything changed, she said, when she was invited to attend the fourth annual powwow at Wiikwemkoong in 1964. She said that while dancing with her relatives to the beat of the powwow drum she suddenly understood herself as an Indigenous woman. The exuberant pride and defiance she witnessed and participated in at the powwow inspired her to accept and honour her heritage. She chose to redirect her artistic work to celebrate and investigate the history and traditions of her people. Her painting style became more graphic, incorporating the sweeping calligraphic lines she had learned from her stone carver grandfather.

Canopy of Protection by Daphne Odjig, 1987

Over the next two decades, Odjig’s style grew to mix her First Nations spiritual heritage with the modernist techniques she had admired years before. Her pluralist approach and two-dimensional representations of indigenous mythology, colonial history, and personal and collective memories relied on vibrant colours and a dark “formline” that anchored the works’ meaning in place.

On her formline, Odjig remarked: “If you looked at my painting before I got my formline on, you probably wouldn’t distinguish what I’m doing. But by the time I got my formline on, everything is in balance, and it’s there.”

“I see my paintings as a celebration of life. My sub-conscious mind may well dictate some content and I’m content to leave it at that. I am uncomfortable with words - my paintings are perhaps my most honest and legitimate statement.”

Her subject matter also changed as she illustrated traditional legends, such as the old trickster tales of Nanabush, and the darker histories of upheaval, land loss and survival.

In 1966, she and her husband Chester Beavon, who was a community development officer for the Department of Indian Affairs, were posted to a small Cree settlement in northern Manitoba. The Chemawawin Cree at Easterville had recently been displaced from their homeland to make way for a dam and generating station.

Inspired by the people’s struggle to cope with the disorder, poverty, and confusion their relocation had caused, Odjig made a series of pen and ink drawings to document the daily life of the community. The intimacy and force of these drawings encouraged her to probe the realities of Indigenous people in Canada even further.

Homage to grandfathers series by Daphne Odjig

Homage to grandfathers series by Daphne Odjig

“I see and feel all aspects of life, and believe that it is all to be shared and recounted. It may not sound “right” to “celebrate” a death, but it was just as important to me to recognize loss and turmoil just as I chose to share joy.”, she told the National Gallery of Canada Magazine in 2014. “To me, it is important not to bury the shame and trauma…”

Odjig has received many awards and recognition for her work, including the Order of Canada and the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts. Her work can be found in public and private collections around the world, including the National Gallery of Canada, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, the Sequoyah National Research Center in Arkansas and the Government of Israel.

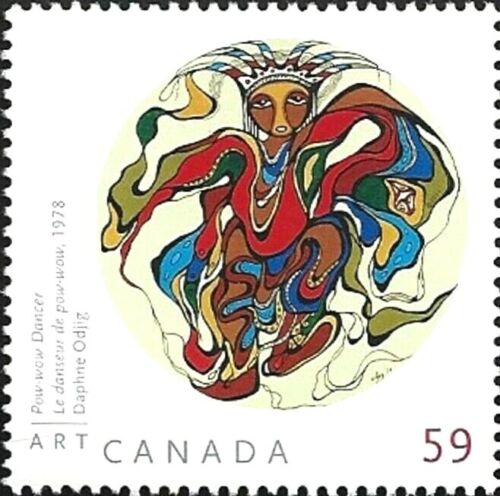

Canada Post stamp celebrating Daphne Odjig

Canada Post stamp celebrating Daphne Odjig

Her work has been part of more than 30 solo and 50 group exhibitions around the world — including a 2009 solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada — and in 2011, Canada Post featured three of her paintings on a series of postage stamps. The United States Postal Service also released stamps depicting her art. Odjig also received the Eagle Feather by Chief Wakageshigon for her artistic achievement.